Over the past five years, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of patients presenting to hospitals with traumatic brain injury. The bulk of these injuries occur in the elderly, and a rapidly growing number of them are taking anticoagulants for management of their medical comorbidities. Although there is a growing body of literature addressing this issue, many practical questions remained unanswered. This is due to the lack of randomized controlled studies of the clinical problems involved. And given the ethical issues of obtaining consent for them, there likely never will be.

An interdisciplinary group of Austrian experts was convened last year to consider the most common questions asked about TBI and concomitant anticoagulant use. They reviewed the existing literature from 2007 to 2018 and combined it with their own expertise to construct some initial answers to those questions.

Over the course of my next few posts, I’ll dig into each of the questions and review their suggested answers. And remember, all these Q&A apply to patients with known/suspected TBI with known/suspected oral anticoagulant use.

Let’s start with some diagnosis questions.

Q1. Should head CT be performed in all patients with known or suspected TBI and suspected or known use of anticoagulants?

Answer: All patients with TBI and potential or known use of anticoagulants should undergo an initial screening CT scan of the head.

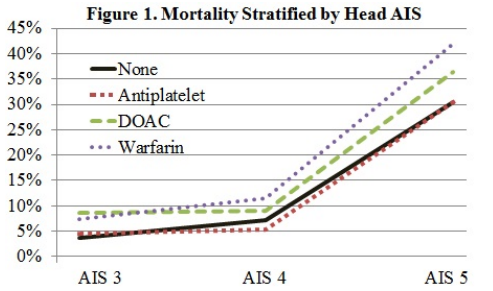

A number of systems that predict the utility of head CT already exist (e.g. Canadian head CT rules). However, they do not and cannot take into account the various permutations of drugs and other medical conditions that may influence coagulation status. Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) like warfarin have been clearly shown to increase mortality after TBI. Data involving the use of anti-platelet agents or direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) are a bit less clear.

Q2. Should a repeat head CT scan be repeated in these patients, and if so, when?

Answer: Patients with intracranial hemorrhage on their initial scan should have a repeat within 6-24 hours, based on the location of the bleed.

The natural course of patients who have an identified intracranial hemorrhage is extremely unpredictable. For that reason, a repeat scan is suggested. However, there are no consistent data that would indicate when this should occur. Indications and potential for progression vary by type of bleed (subarachnoid, subdural, epidural, intraparenchymal). Thus, you must work with your neurosurgeons to arrive at a reasonable repeat interval, and it may be different for a high-risk location (epidural) vs one with low risk (subarachnoid).

Q3. Should a patient with an initial head CT that is negative be admitted for neurologic monitoring?

Answer: Patients taking only aspirin with GCS 15 and initially negative head CT may be discharged. All other patients should be admitted for at least 24 hours for neurologic monitoring as follows (q1 hr x 4 hrs, q2 hr x 8 hrs, q4 hr x 12 hrs). Repeat head CT is indicated if there is any deterioration in neurologic exam.

Multiple papers have described the occurrence of delayed intracranial hemorrhage in patients taking oral anticoagulants other than aspirin. Although some bleeds may develop days or weeks after the initial injury, the majority occur during the first 24 hours. Routine repeat head CT in this group of patients with an initially negative scan has not been found to be helpful.

Q4. What about patients with an initially negative head CT who cannot be examined neurologically (intubation, sedation, dementia)?

Answer: Unexaminable patients should undergo a repeat head CT within 6-24 hours based on the underlying risk factors for development of delayed hemorrhage.

There is no real literature on this topic, but this statement makes sense. Each center should pick a reasonable time interval and include it in their own practice guideline.

In my next post, I’ll review the panel’s recommendations on coagulation tests and target levels for reversal of the various classes of anticoagulants.

Reference: Diagnostic and therapeutic approach in adult patients with traumatic brain injury receiving oral anticoagulant therapy: an Austrian interdisciplinary consensus statement. Crit Care 23:62, 2019.