Spondylosis. Spondylolisthesis. Spondylitis. These words are tossed about blithely by our orthopedic and neurosurgical spine colleagues. But many trauma professionals are confused by the terms. What do they mean? What do they look like?

Let’s start with the root of the word, spondylo… This part is derived from the Greek word spondylos, meaning spine. Now let’s combine it with some of the usual suffixes.

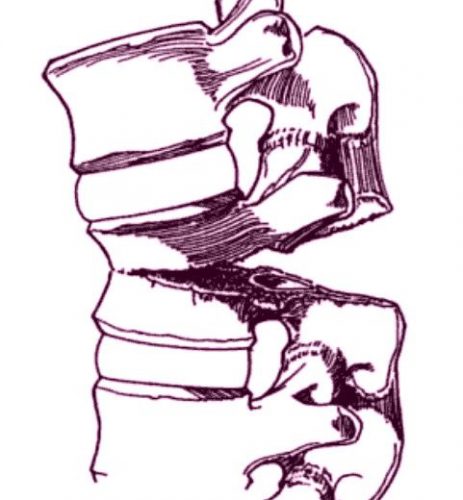

The first one is -osis, so this creates the word spondylosis. Although -osis can denote the “condition of being a …”, in medicine it frequently means a disease or pathological process. Think diverticulosis of the colon. Spondylosis usually denotes a degenerative process of the spine. This is typically due to arthritis and results in bone spurs and disc narrowing. Here is an image of a spine with significant spondylosis:

Now let’s add -listhesis. This is another Greek word that means “slipping or falling.” So in this case, the full word means one vertebra slipping over another. Here’s an image of an anterior spondylolisthesis:

Finally, let’s add -itis. This is the Greek suffix for inflammation. So spondylitis is an inflammatory process of the spine. This can be due to infectious or autoimmune causes. One of the more common types is ankylosis spondylitis, which is an autoimmune variant of rheumatoid arthritis. This causes inflammation of the facet joints and the stabilizing ligaments, leading to fused vertebra and a characteristic patient posture. Here’s a rather extreme case:

I hope this little vocabulary lesson has been helpful. Now go impress your spine specialty colleagues!