I came across an interesting paper in the Journal of Trauma & Acute Care Surgery Open recently. I always read these articles a bit more critically, though, because the peer review process just doesn’t feel quite the same to me as the more traditional journal process. But maybe it’s just me.

In this paper, the authors decided to look at the incidence of delayed hemothorax because “emerging evidence suggests HTX in older adults with rib fractures may experience subtle hemothoraces that progress in a delayed fashion over several days.” They cite two references to back up this rationale.

They retrospectively reviewed records from two busy US Level I trauma centers for adults age 50 or older who were diagnosed with delayed hemothorax (dHTX). Delayed was defined as 48 hours or more after initial chest CT showed either a minimal or trace HTX. The authors went on to analyze the characteristics and demographics of the patients involved.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 14 older adults experienced dHTX after rib fractures, an overall incidence of 1.3% (!)

- About half were diagnosed during the initial hospitalization for the fractures

- All patients had multiple fractures, with an average of 6 consecutive ones; four had a flail chest

- One third progressed from a trace HTX, two thirds had a completely negative initial chest CT

- Only one third were taking anticoagulants or anti-platelet agents

- Patients with multiple fractures, posteriorly located, and displaced were most likely to develop dHTX

The authors concluded that “delayed progression and delayed development of HTX among older adults with rib fractures require wider recognition.”

Bottom line: Really? First, I looked at the papers cited by the authors as the rationale for doing this study. They each found dHTX in about 10% of patients, but their definition was very broad: any fluid visible on upright chest x-ray. Furthermore, the patients were not really “older” either. Average age was around 50.

So I’m not sure yet whether this is a problem, especially with the low incidence of 1.3%. This study doesn’t come right out and state how many patients they reviewed to find their 14, but it can be calculated to be 14 / 1.3% = 1,177. This incidence is only one tenth of that found in the two studies cited. Seems relatively uncommon, and half were discovered while the patients were still in the hospital. Thus only 0.65% sought readmission for chest discomfort or difficulty breathing.

This study required chest CT for rib fracture diagnosis. Is all that radiation (and possibly contrast) really necessary? And did these patients get another chest CT to delineate the pathology? More radiation?

Overall, this paper was not very helpful to me. Yes, I have seen patients come back days or weeks later with a hemothorax that was not seen during their first visit. It’s just that this study raises many more questions that should have been easily answered in the discussion. But they weren’t.

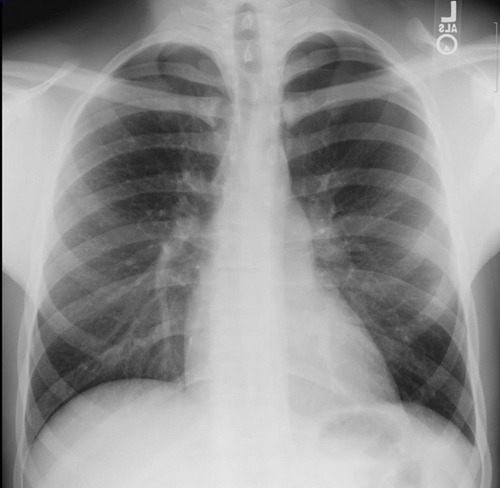

Given that only about a half of a percent of rib fracture patients develop delayed hemothorax after discharge, it is probably prudent to provide information to the patient recommending they see their practitioner if they develop any symptoms days or weeks later. And a simple chest x-ray should do.

Reference: Complication to consider: delayed traumatic hemothorax in older adults. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 2021;6:e000626. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000626.