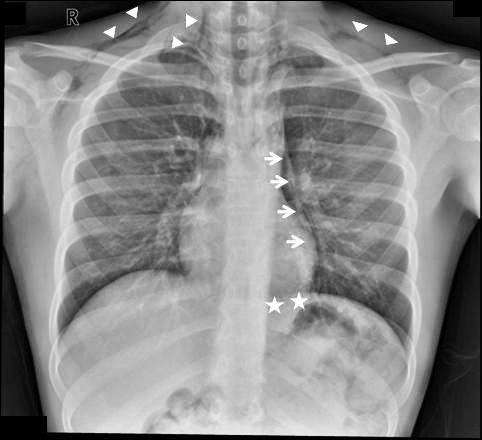

Finding pneumomediastinum on a chest xray or CT scan always gets one’s attention. However, seeing this condition after a simple fall from standing is very simple to evaluate and manage.

There are 3 potential sources of gas in the mediastinum after trauma:

- Esophagus

- Trachea

- Smaller airways / lung parenchyma

Blunt injury to the esophagus is extremely rare, and probably nonexistent after just falling down. Likewise, a tracheal injury from falling over is unheard of. Both of these injuries are far more common with penetrating trauma.

This leaves the lung and smaller airways within it to consider. They are, by far, the most common sources of pneumomediastinum. The most common pattern is that this injury causes a small pneumothorax, which dissects into the mediastinum over time. On occasion, the leak tracks along the visceral pleura and moves directly to the mediastinum.

Management is simple: a repeat chest xray after 6 hours is needed to show non-progression of any pneumothorax, occult or obvious. This image will usually show that the mediastinal air is diminishing as well. There is no need for the patient to be kept NPO or in bed. Monitor any subjective complaints and if all progresses as expected, they can be discharged after a very brief stay.

Tomorrow: A more interesting (and complicated) case of pneumomediastinum.