You’ve undoubtedly read this trite phrase somewhere in your training: “Kids aren’t just small adults!” There are many examples where this is absolutely true. Think about arterial extravasation in solid organ injury. Or severe traumatic brain injury. There are major differences in treatment aggressiveness for both of these.

But what about the code situation? I’ve noted a peculiar phenomenon over the years with regard to pediatric codes of all kinds. Adults tend to persist far longer at resuscitative efforts over children than they normally would on other adults. And what about that most extreme code situation, the emergency thoracotomy?

I’ve also seen the use of this procedure in children who don’t meet the usual adult criteria. But they are kids, right? They can bounce back from more severe insults, right? I hope that I’ve convinced you over the years that one can’t just assume and generalize anything. Things that seem like so much common sense often turn out to be wrong. Think back to the days of the stress / spicy food theory of peptic ulcer disease. This seems so silly now that we recognize the role of H. Pylorii.

Scripps Mercy adult and Rady Children’s Hospital pediatric trauma centers in San Diego performed an extensive review of the National Trauma Data Bank over a three year period. They focused on patients 16 years of age or less who underwent ED thoracotomy within 30 minutes of arrival at the trauma center. They focused on procedure indications and the eventual outcomes.

Here are the factoids:

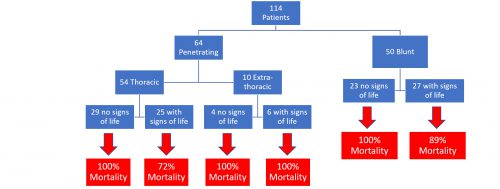

- A total of 114 patients were recorded in the NTDB, with a mean age of 10 years and median Injury Severity Score of 26 (this is the three year experience in the entire US in three years!)

- Males were disproportionately involved at 69%, although this is less than in adults

- Thoracotomy was performed promptly, with a median time after arrival of 5 minutes

- Mechanism of injury was almost evenly split between penetrating (56%) and blunt (44%)

- Blunt mechanism mortality was 94% vs 88% for penetrating

- Penetrating injury outside of the thorax was uniformly fatal

- Patients without signs of life on arrival, regardless of mechanism, also had a 100% mortality rate

- Treatment at an adult trauma center, freestanding pediatric center, or combined center had no impact on these dismal outcomes

Bottom line: This is an interesting paper, and shows that the outcomes after ED thoracotomy in kids is even more dismal than in adults. This is particularly true for children arriving without vital signs and for penetrating abdominal trauma.

However, the authors go on to suggest a practice guideline for pediatric emergency thoracotomy similar to the EAST adult guidelines based on their study findings. However, I think this is ill advised. Have a look at the absolute numbers:

The largest subgroup has only 29 patients in it. These numbers are way too small to consider a guidelines change.

This paper shows that kids are just small adults when it comes to ED thoracotomy. And they seem to do even more poorly with no vital signs or penetrating injuries outside of the chest. So think carefully the next time you must consider this procedure in a child.

Reference: Nationwide Analysis of Resuscitative Thoracotomy in Pediatric Trauma Time to Differentiate from Adult Guidelines? J Trauma published ahead of print, July 6, 2020.