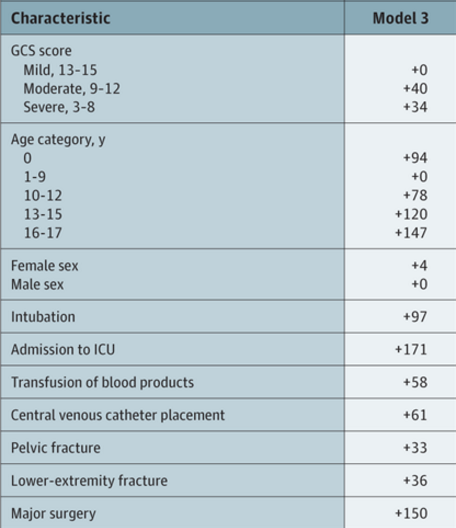

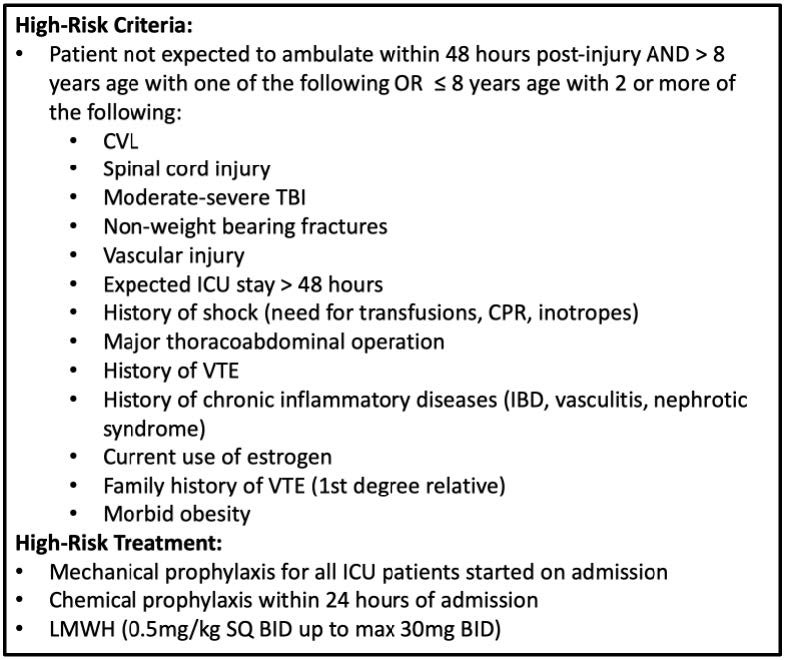

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) after trauma in adults has generated a considerable body of literature for guidance. However, there is much less information available regarding pediatric trauma. High-risk criteria for pediatric VTE after trauma have recently been released.

These criteria have not yet been evaluated prospectively or coupled with the administration of chemoprophylaxis. The Medical College of Wisconsin trauma group organized a prospective, multi-institutional study involving eight pediatric trauma centers. They studied VTE events within 30 days and bleeding complications. The children were stratified into three groups: no prophylaxis, early prophylaxis (within 24 hours), and late prophylaxis.

Here are the factoids:

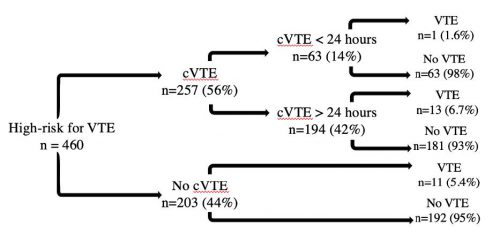

- A total of 460 patients were enrolled during a three-year period

- The number of VTE events was very low at 25 (5.4%)

- Patients who developed VTE had a median of 4 of the high-risk criteria, most commonly ICU stay>48 hours and TBI.

- Half of patients received prophylaxis

- VTE occurred in 1.6% receiving an early dose and 6.7% with late dosing

- There were no bleeding complications

The authors concluded that prophylaxis in children at high risk for VTE was safe, but they could not demonstrate any risk reduction for those who had received chemoprophylaxis compared to those who had not.

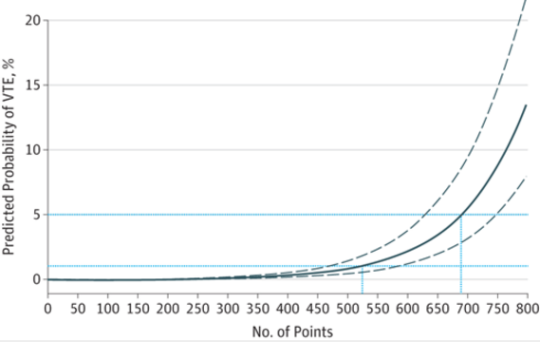

Bottom line: This is another study that was cursed by low numbers. See the breakdown chart below:

There is a trend toward higher VTE in children receiving prophylaxis late or never. However, the number of subjects is far too low to detect significance. The good news is that there were no bleeding events in this modest sample of 257 patients.

So what next? The authors state that “further subgroup analysis is ongoing to refine the high-risk criteria.” Good luck with that because subgrouping will deplete the numbers even further.

There are several things the authors could do to improve this work:

- Get more subjects! Increase the number of centers participating, and consider sending it through the EAST Multicenter Trial process.

- Streamline the list of high-risk criteria. There are quite a few of them. Try to focus on the most obvious ones and make sure each one has clear definitions. And set a threshold of how many must be present to trigger chemoprophylaxis.

- Define the pediatric patient precisely. As children approach puberty, they behave more like adults as it pertains to VTE. State an explicit age cutoff.

This presentation should be a springboard to soliciting help from other pediatric trauma centers so this group can return to this meeting with compelling information.

Reference: The No Clot VTE study in high-risk pediatric trauma patients. EAST 2024 Podium paper #6.