Diaphragm injury from blunt trauma is uncommon, occurring in only a few percent of patients after high-energy mechanisms. They usually occur on the left side and are more frequently seen after t-bone type car crashes and in pedestrians struck by a car.

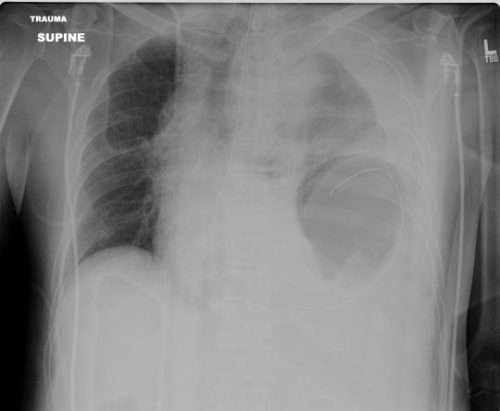

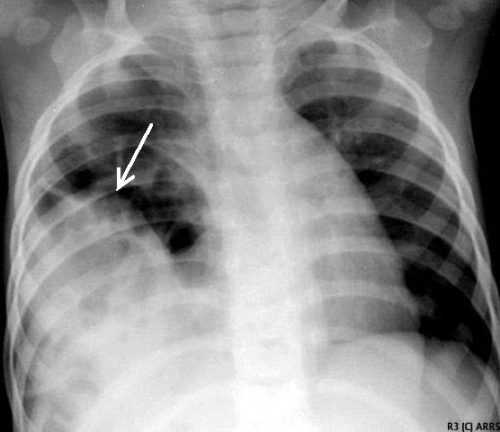

Blunt diaphragm injury on the right side is very unusual. Even so, it is more easily detected due to obvious displacement of the liver that can be seen on chest x-ray. Blunt injuries on the right side usually result in a large rent in the central tendon or detachment of the diaphragm from the chest wall. This allows the liver to herniate into the chest, and the chest x-ray finding is not subtle.

This image shows an acute herniation of the liver through the diaphragm. Due to the size of the liver, only part of it can typically fit through the rent. Radiologists call this the “cottage loaf” sign. Why? Here’s the bakery item it is named after. Get it now?

Thankfully, most of these injuries are identified in the acute setting. They must be addressed surgically because, if left untreated, more and more of the liver will slowly move into the chest resulting in respiratory problems in the long run.

Acute management usually consists of laparotomy to address both the diaphragm tear and any other associated intra-abdominal injuries. The liver should be reduced by sliding a hand next to it laterally into the chest cavity and pushing the dome downwards. The right triangular ligaments should be taken down (if they are not already destroyed) to mobilize the organ better so the diaphragm laceration can be closed. This is typically accomplished with some type of large (size 0) permanent suture. A chest tube will be needed to evacuate the iatrogenic pneumothorax created by opening the abdomen.

Chronic right diaphragm injuries are a different animal entirely. There is no longer any need to evaluate for intra-abdominal injury, so the procedure is usually performed through the chest. For smaller injuries, thoracoscopic procedures have been described that push the liver downwards and then either suture the diaphragm primarily or (more likely) incorporate a piece of mesh.

Larger injury requires conversion to an open procedure so more muscle power can be used to push the liver downwards to facilitate the repair. However, do not underestimate the adhesions that will be present between diaphragm and liver (and possibly the lung) in long-standing injuries. It may take some time to dissect them away. Rarely, a laparotomy (or laparoscopy) may be needed to assist for very large and complex injuries.

References:

- Management of Delayed Presentation of a Right-Side Traumatic

Diaphragmatic Rupture. World J Surg 36:260-265, 2012. - Delayed Discovery of Diaphragmatic Injury After Blunt Trauma:

Report of Three Cases. Surg Today 35:407-410, 2005.