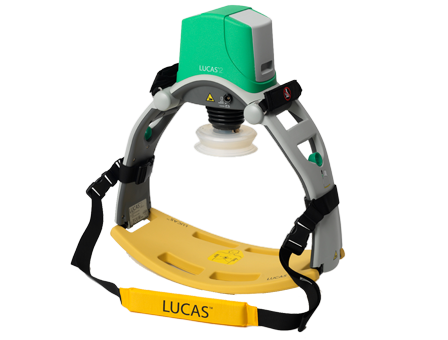

Here’s an image of the Lucas automated CPR device. Here’s a question for you: can you use the Lucas chest compression device in a pregnant patient?

The official company answer is “no.” Obviously, this is one those areas that is tough to get research approval on, and the number of pregnant patients who might need it is very small. So basically, we have little experience to go on.

That being said, the reality is that prehospital agencies can and do use it for these patients on occasion. There is only one published case report that I could find (see reference below). The thing that makes using this device a little more challenging is that, to optimize blood pressure, late term pregnant patients need to have the uterus rolled off of the vena cava. This means tipping the patient to her left.

As you can see from the picture above, the design of the Lucas makes this a bit difficult. However, it can be done, either by tipping the board the patient is on or wedging something under the right side of the back plate.

And as always, make sure that you adhere to your local policies and procedures, or have permission from your medical director to use this device in this particular situation.

Reference: Cardiac arrest and resuscitation with an automatic mechanical chest compression device (LUCAS) due to anaphylaxis of a woman receiving caesarean section because of pre-eclampsia. Resuscitation 68(1):155-159, 2005.