The shift toward initial nonoperative management of spleen injuries began in the early 1990’s, as the resolution of early CT scans began to improve. Our understanding of the indicators of failure also improved over time, and success rates rose and splenectomy rates fell.

Angiography was adopted as an adjunct to early management, especially when we figured out what contrast extravasation and pseudoaneurysms really meant (bad news, and nearly certain failure in adults). At first, it was used in a shotgun approach in most of the higher grade injuries. But we have refined it over the years, and now it is used far more selectively at most centers.

A group at Indiana University was interested in looking at the impact of angio use on splenic salvage over a long time frame. They queried the National Trauma Data Bank, looking specifically at high grade splenic injury care at Level I and II centers from 2008-2014. Patients undergoing splenectomy were divided into early (<= 6hr after admission) and late (> 6 hrs). Over 50,000 records were analyzed.

Here are the factoids:

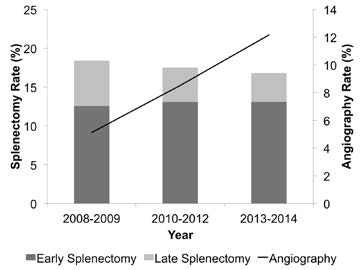

- There was a shift from early splenectomy to late splenectomy over the study period that was statistically significant

- Use of angio increased from 5 to 12% during the study period

- Overall splenectomy rate remained about the same

So the authors recognize that late splenectomy has decreased. But they also state that early splenectomy has increased. They attribute it to increased recognition of patient requiring early splenectomy. They then call into question the need to use angiography if it hasn’t decreased the overall splenectomy rate.

Problem: The early splenectomy rate increased from about 13% to 14%, reading their graph, and is probably not significant. These are the failures that occur in the trauma bay and shortly thereafter that must be taken to the OR. The late splenectomy rate decreased from 5% to 3%, which may be significant (p value not included in the abstract). These are failures during nonoperative management, and are decreasing over time. And BTW, the authors do not define what “high grade” splenic injuries they are looking at.

Bottom line: This abstract illustrates why it is important to read the entire article, or in this case, listen to the full presentation at AAST. It sounds like one that’s been written to justify not having angiography available as it is currently required.

The authors showed that overall splenectomy rate was the same, but delayed splenectomy (late failure) has decreased with increasing use of angiography. But remember, this is an association, not cause and effect. Most of the early failures are still probably ones that can’t be prevented, but we’ll see if the authors can dissect out how many went to OR very early (not eligible for angio), or later in the 6 hour period (could have used angio). It looks to me like the use of angiography is having the desired effect. But undoubtedly we could use that resource more wisely. What we really need are some guidelines as to exactly when a call to the interventional radiologists is warranted.

Related posts:

Reference: Overall splenectomy rates remain the same despite increasing usage of angiography in the management of high grade blunt splenic injury. AAST 2016, paper 35.