Angiography and angioembolization (AE) have helped trauma professionals stop pesky bleeding from the pelvis, solid organs, and other hard to reach places for decades. The American College of Surgeons has recognized its importance and even has a specific criterion for interventional radiologist response times.

Many centers have found this 30-minute response for radiologist arrival to be onerous. So, of course, someone decided to look at the data to see if it was really warranted. The group at the University of Arizona at Tucson did a big data dive using the Trauma Quality Improvement Program database to try to tease out the consequences of prompt vs delayed access to AE in blunt trauma patients.

Four years of TQIP data were analyzed. The authors focused on the records of patients who underwent AE within 4 hours of arrival for blunt injury to liver, spleen, or kidney. They excluded transfers in, burn patients, and those who underwent an operation prior to AE. The 4 hour AE period was subdivided into hourly segments and outcomes were examined for each.

Here are the factoids:

- Out of over a million records, 924 met study inclusion criteria

- Patients were relatively young with a mean age of 44, and seriously injured with a median ISS of 29

- Spleen injuries were most common (64%), followed by liver (50%), and kidney (27%)

- Overall 24 hour mortality was 5% and in-hospital mortality was 15%

- The 24 hour mortality significantly increased as each hour passed until AE, from 2% to 24%.

- On multivariate analysis, in-hospital mortality showed the same hourly increase

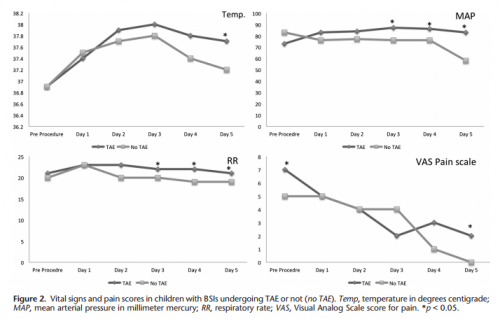

- No differences in the amount of blood, plasma, or platelets given were noted in any of the groups

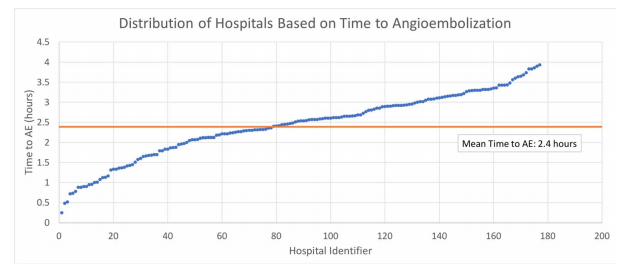

- Average time to AE correlated with trauma center AE volume, with 1.6 hours at centers doing more than 14 cases per year to 2.7 hours at those doing less than 9 cases

The authors concluded that delayed AE for solid organ injury resulted in increased mortality without any difference in transfused blood products. They encouraged centers to ensure rapid access to this vital procedure.

Bottom line: This is an important paper. Other research on angiography in blunt trauma has not shown the survival differences that we see here. But they did not focus on patients who underwent actual embolization. This one shows that time to AE is very important in those patients who really need it.

It appears that the most important factor is door to angiography suite time. There are many factors involved, though. First, the specific injury must be recognized by the clinicians. This involves access to CT, timeliness of radiologist report, decision making by the trauma professional, and timeliness of response by the interventional radiologist and the IR team.

Most centers focus only on that 30-minute response time required of the interventionalist. But as you can see, there are many more moving parts. I would urge all centers to look at their door to AE time and compare to what was found in this study. If you find that it is taking more than an hour and a half, it’s probably time for a PI project to tighten it up. This is particularly important in centers with low AE volume.

Reference: Angioembolization in intra-abdominal solid organ injury: Does delay in angioembolization affect outcomes? J Trauma 89(4):723-729, 2020.