In my previous post, I described the early days of penetrating neck injury management and introduced a paper suggesting that this concept should be revised. Today, I will summarize a paper by Siletz and Inaba that is currently in press and outlines what the contemporary way of treating these injuries should be.

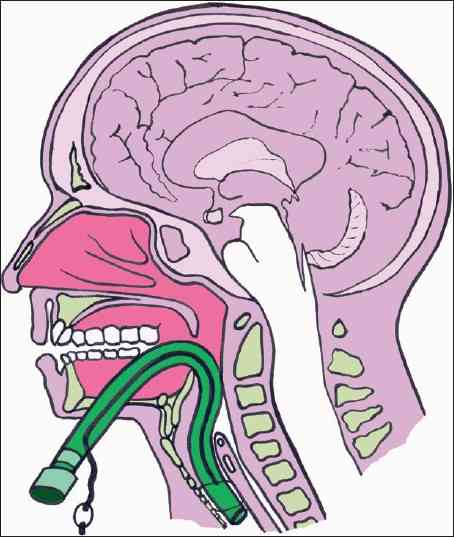

Step 1. If present, rapidly control external hemorrhage and airway compromise. As always, bleeding should be controlled by direct pressure or packing. Direct pressure does not look like this:

The goal is to create a zone of pressure higher than the systolic BP perfectly in the area of bleeding. Since pressure is force per unit area, a larger area like that show above diffuses the maximum pressure and just doesn’t work. Note the ongoing bleeding shown in the picture.

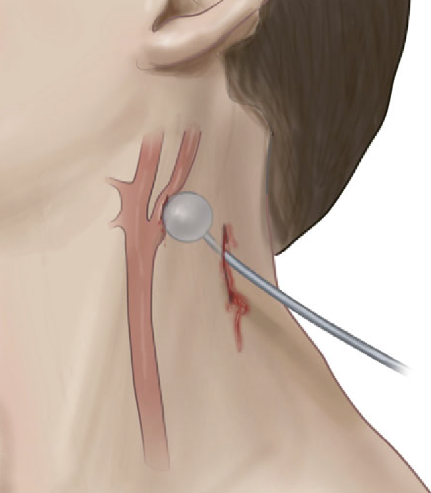

Here’s what direct pressure looks like:

Or

A single finger (or maybe two) should be placed on or in the wound. If deeper bleeding is a problem, the same kind of pressure can be accomplished by packing with gauze. If gauze is used, however, pressure must usually be applied over the gauze to make sure that the underlying tissues remain pressurized.

If gauze packing is not practical because of this need for additional pressure, a urinary catheter can be inserted into the wound and inflated until the bleeding stops.

Courtesy Core EM

Airway control should ideally occur in the operating room. Given the proximity of this wound to airway structures, it is imperative that an ideal environment is present when the airway is inserted. A skilled anesthesiologist should be present, with difficult airway equipment available if needed. The surgeon should be standing by with all equipment needed to obtain a surgical airway if needed. Even though the patient may be breathing okay, the airway structures may be distorted by hematoma or injury.

You have probably noted that this is the same initial assessment we used in the old three zones approach. In the next post, I will discuss the details of a new assessment approach that considers the neck a single unit.