It’s been five years since I published my Laws of Trauma, and it’s time to dust them off again. In the meantime, I’ve added a couple of new ones.

But before I start publishing them next week, I’d like to take a moment to share “McSwain’s Rules of Patient Care.” I met Norm McSwain when I was junior faculty at the University of Pennsylvania. As so many of his era were, he was larger than life. He was friendly, outgoing, animated, and a real champion for quality trauma care.

Norm was a skilled surgeon and teacher, but his achievements were felt far outside his home in Louisiana. He was an early member of the ACS Committee on Trauma, and was very involved in the development of the Advanced Trauma Life Support and Prehospital Trauma Life Support courses. He is credited with developing the original EMS programs in both Kansas, where he took his first faculty position out or residency, and in New Orleans, his home for the remainder of his life. He spent his career at the Charity Hospital there, weathering multiple political storms over the years, as well as the big one, Hurricane Katrina. He was instrumental in achieving Level I Trauma Center status for its replacement, Interim LSU Hospital.

Norm’s accomplishments are, as many of his contemporaries who have left us, too numerous to count. I certainly won’t try to recount them here. But it was his charm, his love for his charges, and his willingness to teach every trauma professional that will always be remembered.

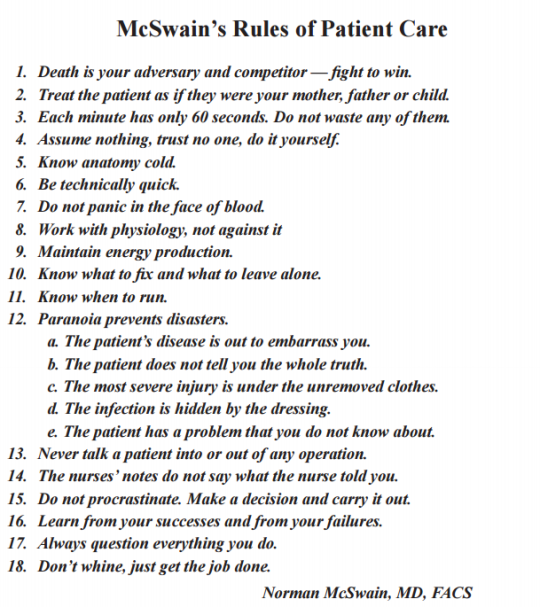

I’ll leave you with his 18 rules of patient care. They are timeless, and will serve you well regardless of your degree and level of medical training.

Download McSwains Rules of Patient Care