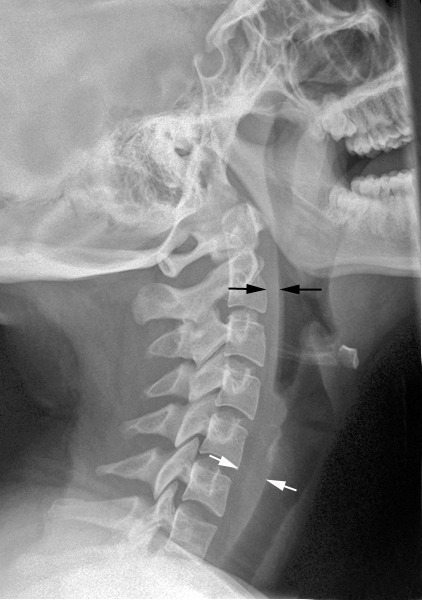

Cervical spine injury presents a host of problems, but one of the least appreciated ones is dysphagia. Many clinicians don’t even think of it, but it is a relatively common problem, especially in the elderly. Swallowing difficulties may arise for several reasons:

- Prevertebral soft tissue swelling may occur with high cervical spine injuries, leading to changes in the architecture of the posterior pharynx

- Rigid cervical collars, such as the Miami J and Aspen, and halo vests all force the neck into a neutral position. Elderly patients may have a natural kyphosis, and this change in positioning may interfere with swallowing. Try extending your neck by about 30 degrees and see how much more difficult it is to swallow.

- Patients with cervical fractures more commonly need a tracheostomy for ventilatory support and/or have a head injury, and these are well known culprits in dysphagia

Normal soft tissue (<6mm at C2, <22mm at C6)

A study in the Jan 2011 Journal of Trauma outlined the dysphagia problem seen with placement of a halo vest. They studied a series of 79 of their patients who were treated with a halo. A full 66% had problems with their swallowing evaluation. This problem was associated with a significantly longer ICU stay and a somewhat longer overall hospital stay.

Bottom line: Suspect dysphagia in all patients with cervical fractures, especially the elderly. We don’t use halo vests very often any more, but cervical collars can exacerbate the problem by keeping the neck in an unaccustomed position. Carry out a formal swallowing evaluation, and adjust the collar (or halo) if appropriate.

Reference: Swallowing dysfunction in trauma patients with cervical spine fractures treated with halo-vest fixation. J Trauma 70(1):46-50, 2011.