Compression Of The Fractured Pelvis With A Sheet

Fractures of the posterior pelvis are notorious for their potential to bleed. Here are some tips to use if you encounter a trauma patient with an unstable pelvis and want to slow down the bleeding in the ED.

First, figure out what type of pelvic fracture it is. You will probably be able to do this using physical exam and a simple A-P radiograph. Push down hard on the anterior superior iliac spines to see if the pelvis moves. If so, the patient has an anterior-posterior compression type fracture, and you will likely see diastasis of the pubic bones on the xray. These are amenable to compression maneuvers discussed here.

If the pelvis collapses with lateral compression of the iliac wings, then the patient has a lateral compression fracture and compression maneuvers should not be used. Similarly, if a vertical shear is seen on the xray, do not use compression maneuvers.

There are several pieces of equipment available to help compress the pelvis:

- Commercial pelvic compression product (e.g. T-Pod). These are convenient but pricey.

- MAST trousers – just inflate the abdominal compartment, not the legs. But who has these laying around any more?

- Sheet – cheap and quick. Very effective if used properly.

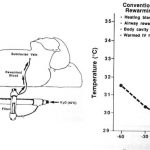

To apply a sheet, it needs to be folded into a narrow band no more than 12 inches high. It should be passed under the patient’s legs and moved upwards. It must be centered over the greater trochanters. This will apply proper pressure, but will not cover the lower abdomen (think laparotomy) or the genitalia (think urinary catheter). Cross the ends of the sheet over as shown above, with one person holding the cinch point while the sheet is secured. This can be carried out with a knot or plastic clamps. Metal clamps will degrade CT or angiographic imaging and should not be used. The sheet should be left in place for the shortest period of time possible, as skin breakdown can occur.

The picture above on the left shows a sheet that is folded too wide (difficult to get enough tension, and covers the good stuff) and uses metal towel clips. The picture on the right shows the proper technique.