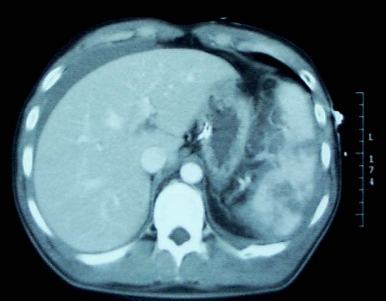

Any trauma professional who has dealt with spleen injuries knows that the white blood cell (WBC) count rises afterwards. And unfortunately, this elevation can be confusing if the patient is at risk for developing inflammatory or infectious processes that might be monitored using the WBC count.

Is there any rhyme or reason to how high WBCs will rise after injury? What about after splenectomy or IR embolization? An abstract is being presented at the Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons next month that examines this phenomenon.

This retrospective study looked at a convenience sample of 75 patients, distributed between patients who had splenic injury that was either not treated, removed (splenectomy), or embolized. Data points were accumulated over 45 days.

Here are the factoids:

- 20 patients underwent splenectomy, 22 were embolized, and 33 were observed and not otherwise treated

- Injury severity score was essentially identical in all groups (19)

- Splenectomy caused the highest WBC counts at the 30 day mark (17.4K)

- Embolized patients had mildly elevated WBC levels (13.1K) that were just above the normal range at 30 days

- Observed patients had high normal WBC values (11.0K) after 30 days

- Values in observed and embolized patients normalized to about 7K after 30 days; splenectomy patient WBC count remained mildly elevated at 14.1K.

- The authors concluded that embolization does not result in permanent loss of splenic function (bad conclusion, rookie mistake!)

Bottom line: This study is interesting because it gives us a glimpse of the time course of leukocytosis in patients with injured spleens. If you need to follow the WBC for other reasons, if gives a little insight into what might be attributable to the spleen. Splenectomy generally results in a chronically elevated WBC count, which tends to vary in the mid-teens range. Embolization (in this study) transiently elevates the WBC count, but it then drops back to normal.

The big problem with this study (besides it being small) is that it fails to recognize that there are many different shades of embolization. Splenic artery? Superselective? Selective? I suspect that the WBC count in main splenic artery embolization may behave much like splenectomy in terms of leukocytosis. And the conclusion about splenic function being related to WBC count was pulled out of a hat. Don’t believe it.

Reference: Leukocytosis after Splenic Injury: A Comparison of Splenectomy, Embolization, and Observation. American College of Surgeons Scientific Forum Abstracts pg S164, 2015.