Today’s post is another review of some of the practice guidelines published by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). This one covers the evaluation and management of diaphragmatic injury.

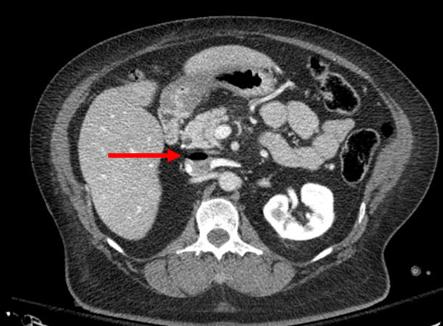

Diaphragm injury is a troublesome one to diagnose. It is essentially an elliptical sheet of muscle that is doubly-curved, so it does not lend itself well to diagnosis by axial imaging. Addition of sagittal and coronal reconstructions to a thoraco-abdominal CT has been helpful, but still has a far from perfect diagnostic record.

From an evaluation standpoint, there are several possibilities:

- Observation – not generally recommended. It is usually combined with imaging such as chest x-ray to see if interval changes occur that would indicate the injury.

- Chest x-ray – this is not often diagnostic, but when herniation of abdominal contents is obvious the patient most assuredly has an operative problem.

- Thoraco-abdominal CT scan – this technology keeps getting better, especially with thinner cuts and different planes of reconstruction. Sometimes even subtle injuries can be detected. But this exam is still imperfect.

- Laparoscopy or thoracoscopy – this technique yields excellent accuracy when the injury is in an area that can be viewed from the operative entry point chosen.

- Laparotomy or thoracotomy – this is the ultimate choice and should be nearly 100% accurate. It is almost the most invasive and has more potential associated complications.

EAST reviewed a large body of literature and selected 56 pertinent papers for their quality and design. They critically reviewed them and applied a standard methodology to answer several questions.

Here are the questions with the recommendations from EAST, along with my comments:

- Should laparoscopy or CT be used to evaluate left-sided thoraco-abdominal stab wounds? First, these patients must be hemodynamically stable and not have peritonitis. If either is present, there is no further need for diagnosis; a therapeutic procedure must be performed.

Left sided diaphragm injuries from stabs are evil. The hole is small, and since the pressure within the abdomen is greater that the chest, things always try to wiggle their way through this small hole. It can remain asymptomatic if the wiggler is just a piece of fat, but can be catastrophic if a bit of the stomach or colon pushes through and becomes strangulated. Furthermore, these holes enlarge over time, so more and more stuff can push up into the chest.

EAST recommends the use of laparoscopy for evaluation to decrease the incidence of missed injury. However, if the injury is in a less accessible location (posterior), the patient has body habitus issues, or adhesions from previous surgery may lead to incomplete evaluation, laparotomy should be strongly considered. - Should operative or nonoperative management be used to evaluate right-sided thoraco-abdominal penetrating wounds? Note that this is different than the last question. All penetrating injuries are included (stabs and gunshots), and this one is for management, not evaluation. And the same caveats regarding hemodynamic stability and peritonitis apply. It applies to both stabs and gunshots.

Unlike left-sided injuries, right-sided ones are much more benign. The liver keeps anything from pushing up through small holes, and they do not tend to enlarge over time due to this protection. For that reason, EAST recommends nonoperative management to reduce mortality and morbidity related to operation. - Should stable patients with acute diaphragm injury undergo repair via an abdominal or thoracic approach? This question applies to any diaphragm injury that requires operation, such as right-sided penetrating injury or any blunt injury. EAST recommends an approach from the abdomen to reduce morbidity and mortality. Since abdominal injury frequently occurs in these cases, an approach from the chest limits the ability to identify and repair abdominal injuries. Otherwise, you may find yourself doing a laparotomy in addition to the thoracotomy.

- Should patients with delayed visceral herniation through a diaphragm injury undergo repair via an abdominal or thoracic approach? For years, the preferred approach for delayed presentations has been through the chest because the injury is easier to appreciate and repair. However, if ischemic or gangrenous viscera are present, it will be more difficult to manage and repair from the chest. EAST does not make a specific recommendation for this question and suggests the surgical approach be determined on a case by case basis.

- Should patients with an acute diaphragm injury from penetrating injury without concern for other intra-abdominal injuries undergo open or laparoscopic repair? The quality and quantity of data addressing this question were very low, but EAST recommends laparoscopy for repair of these injuries to reduce morbidity and mortality. This includes blunt injuries, which tend to be larger. There were some conversions to an open procedure, especially in the blunt cases. The usual caveats on exposure, injury location, body habitus and previous surgery apply.

Reference: Evaluation and management of traumatic diaphragmatic injuries: A Practice Management Guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma 85(1):198-207.