Today’s post is directed to all those prehospital trauma professionals out there.

Car crashes account for a huge number of injuries world-wide. About 40% of people involved in them are initially trapped in the vehicle. And unfortunately, entrapped individuals are much more likely to die.

There are four basic groups (and their category in parentheses) of trapped car occupants:

- those who can self-extricate or extricate with minimal assistance (self-extrication)

- individuals who cannot self-extricate due to pain or their psychological response to the event, but can extricate with assistance (assisted extrication)

- people who are advised or choose not to self-extricate due to concern for exacerbating an injury, primarily spine (medically trapped)

- those who are physically trapped by the wreckage who require disentanglement (disentanglement and rescue)

Prehospital providers have several choices to help extricate patients in the second and third categories: encourage self-extrication, rapid extrication without the use of tools, or traditional extrication where the vehicle is cut away to allow egress. The fourth category always requires tools for extrication.

Although rescue services try to minimize or mitigate unnecessary movement of the patient, stuff happens. Large and forceful movement is considered high risk, but smaller movement do occur. This is of particular concern in patients who might have a spine injury.

There have been a number of recent papers suggesting there might be greater benefits to self-extrication. A group of authors in the UK and South Africa designed a biomechanical study to test these methods of extrication in healthy volunteers.

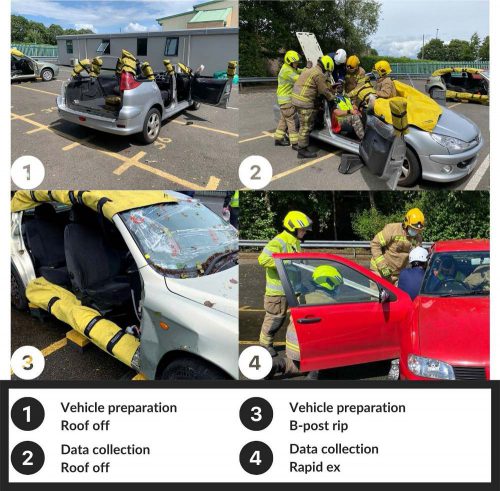

The authors wanted to find out exactly how much movement occurred using the various extrication techniques. The volunteers were fitted with an Inertial Measurement Unit, which measures the orientation of the head, neck, torso, and sacrum in real time. The IMU can detect even very small changes in orientation of the body. The volunteers were placed in a standard 5-door hatchback sedans that were prepared for each type of extrication as seen above.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 230 extrications were performed for analysis

- The smallest amount of maximal and total movement of body segments was seen in the self-extrication group

- The greatest amount of movement was found in the rapid extrication group, with 4x to 5x the movement in the self-extrication group

- The difference in body movement between the self-extrication group and all others was significant

- In general, movement increased as extrication techniques progressed from roof removal to B post removal to rapid extrication

The authors concluded that self-extrication resulted in the smallest amount of movement and the fastest extrication time, and that it should be the preferred technique.

Bottom line: This is the first study that specifically evaluated spinal movement occurring with commonly used extrication techniques. Other similar studies have used a variety of measurement techniques, none of which are as precise as this. One potential weakness with this one is that it used healthy volunteers. But obviously, it is not practical to attempt anything like this with real, injured patients.

Since we know that patients trapped in cars are more likely to die, time is of the essence. This study shows that self-extrication is both fast and safe with respect to spinal movement. The information will assist our prehospital colleagues in making the best decisions possible when faced with patients trapped in their car.

Reference: Assessing spinal movement during four extrication methods: a biomechanical study using healthy volunteers. Scand J Trauma open access 30: article 7, 2022.