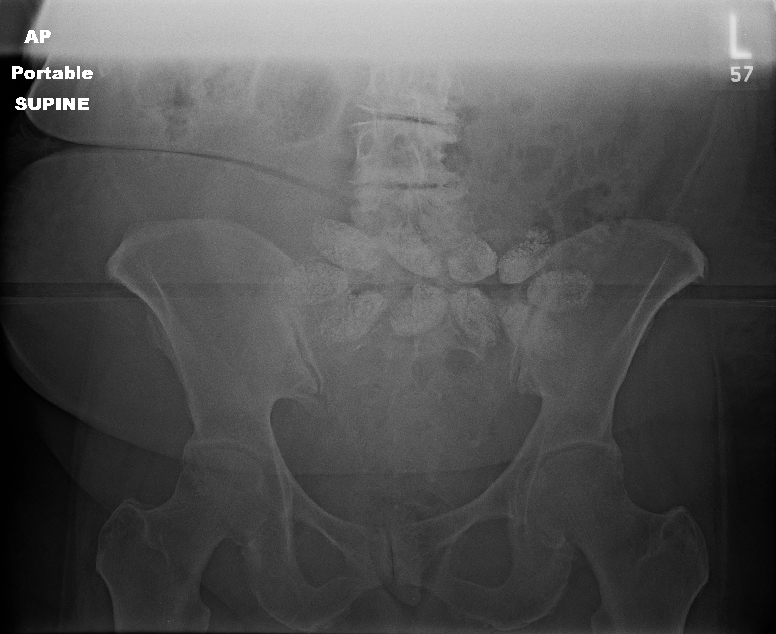

In my last post, I laid out the various options available for initial management of major pelvic fracture bleeding. Today, I’ll compare two of the newer tools: embolization (AE) and preperitoneal packing (PPP). In the next post, I’ll look at the data available for REBOA.

Interestingly, the use of AE and PPP vary geographically. Angioembolization has been a mainstay in the US for some time, and PPP has been more commonly used in Europe. The use of both is becoming more widespread, and each has its pros and cons.

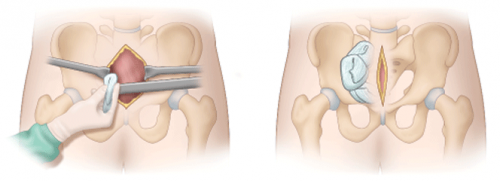

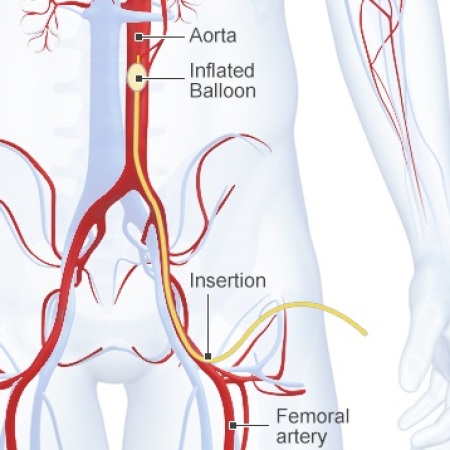

Angioembolization requires the presence of a special interventional radiology team and a reasonably stable patient. The procedure can take some time, and the IR suite is not really the place to house an unstable patient. Preperitoneal packing requires a reasonably stable pelvis to hold the packs in place for optimal tamponade, which may require application of an external fixator at the time of the procedure.

But is one better than the other? A number of relatively small studies have been performed, which means that it is time to synthesize them and see if some clearer answers can be found. The trauma group in Newcastle, Australia did just this. They performed a systematic search of the literature, analyzing the impact of each procedure on in-hospital mortality.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 18 studies met the authors’ inclusion criteria: 6 studies on AE, 9 studies of PPP, and 3 that compared them to each other

- ISS was significantly higher in the PPP group vs AE (41 vs 36)

- Average time to OR in the PPP patients was 60 minutes vs 131 minutes to IR in the AE group (statistically significant)

- A quarter (27%) of the PPP patients did not get adequate hemorrhage control and required AE

- In-hospital mortality in the PPP papers was 23% vs 32% in the AE research

- Mortality in the papers that compared AE directly to PPP wasno different

Bottom line: What does this all mean? Is packing “better” than embolization? The simple answer is that we don’t know yet. Due to the way this study was performed, it is not possible to tease out all of the possible confounders.

We are taught that control of hemorrhage is paramount. The time to definitive management in the AE group was twice that of the PPP patients. This could have a major impact on mortality. Two hours of bleeding can certainly kill. And the lower mortality in the PPP group occurred even though their injury severity was higher.

Many trauma centers have both of these interventions available to choose from. How should we approach their use? Unfortunately the literature is still to scarce to come to strong conclusions. Until we have better research to learn from, I suggest the following:

- Time is of the essence. Which procedure can you get the fastest? In many cases, this will be preperitoneal packing since it’s just a trip to your trauma OR, which should be ready and waiting. If you have an IR team standing by or available very quickly, you could consider them first.

- Pay attention to hemodynamic stability. An IR suite is no place for an unstable patient. The resuscitation equipment is not on par with the OR, and one never knows exactly how long the procedure will last.

- If you have a hybrid room, use it! This is the ideal situation. The surgeon can start the PPP while the orthopedic surgeon applies a fixator. And the radiologist can be preparing to finish it off with a quick squirt as soon as they move away from the groin.

- The use of one does not rule out the other. If one fails and the patient has increasing fluid and blood requirements move immediately to the other procedure to try to get control.

Reference: Preperitoneal packing versus Angioembolization for the initial management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Trauma, publish ahead of print, Jan 4 2022, doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003528.