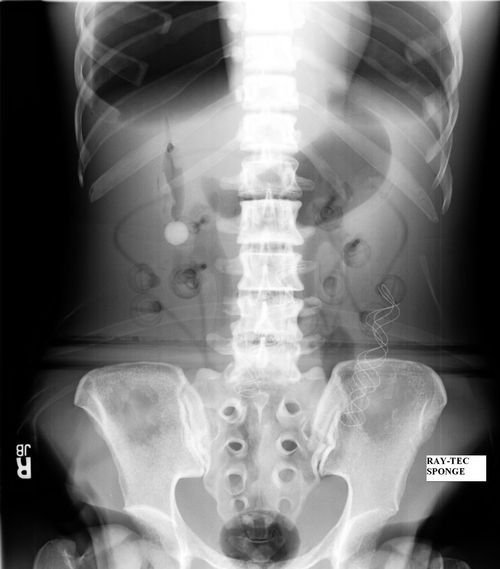

Sponges are unfortunately one of the most common retained foreign bodies. This is due to their small, flimsy nature. The surgeon usually looks at the obviously visible areas of the abdomen or other body cavity before closing. She can also feel around in the “nooks and crannies”, but sponges feel very similar to the other organs surrounding it.

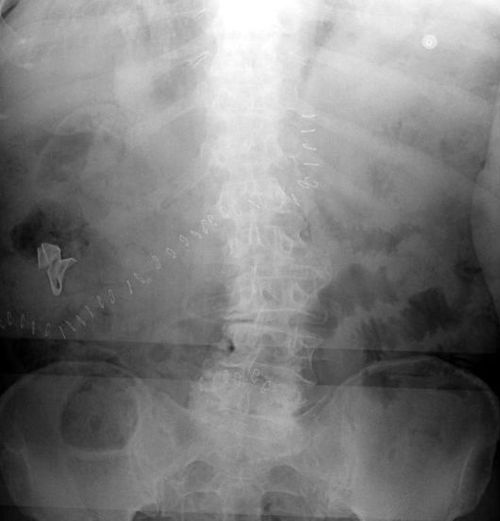

But what about more substantial items, like surgical instruments? Surely these are so obvious as to not leave behind?

Unfortunately, not so. Take a look at these items. This is a large pari of surgical forceps.

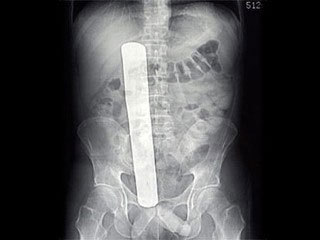

This is a malleable retractor, a long, thin sheet of pliable metal that can be bent to any desired shape.

And finally, a pair of Metzenbaum scissor, a common surgical instrument for cutting tissue.

Bottom line: It doesn’t matter how small or large, anything can and will be left behind in emergent and trauma cases. Recognizing that this can occur, no matter how confident you are that it has not, is the key. Always count, but followup with an x-ray that covers all areas of the surgical field before closing.

Related post: