The concept of performing 4-compartment leg fasciotomy using only one incision is not a new one. Techniques using a lateral approach, either with or without fibulectomy, have been described as early as 1967.

A new paper describes a single-incision technique for compartment syndrome using a medial approach. The authors believe that going through the anterior compartment to release the deep posterior is quicker, uses a smaller flap, and avoids injury to the peroneal nerve. They reviewed their own experience over a 5 year period.

Here are the factoids:

- 180 fasciotomies were performed for compartment syndrome, of which 30 were single-incision

- 27 had associated fractures, 2 were due to soft tissue injury and 1 was spontaneous

- There was a single wound infection, nerve injury, and patient with persistent pain. There were several tethered tendons and scars.

- The number and types of complications were similar to traditional fasciotomy

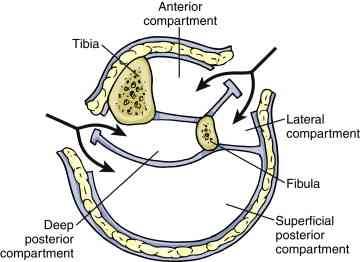

Traditional 4 compartment fasciotomy with 2 incisions. Source: gog.net.nz

Bottom line: Sounds great, right? Yes, it’s a small study, and statistically there is not enough power to show that it’s “better.” So if it’s not worse, and there is just one smaller incision, what’s wrong with it?

For me, the problem is that there is too much opportunity to perform an incomplete fasciotomy. The learning curve for single incision fasciotomy, either this one or the more traditional lateral approach, is steep. Seriously impaired patients who need fasciotomy are frequently not going to be awake any time soon, leaving the surgeon with no neurologic or pain exam.

My recommendation: read papers like this and smile. Then do the classic 2 incision operation, making sure that all compartments are completely released.

Related post:

Reference: A single incision fasciotomy for compartment syndrome of the lower leg. J Ortho Trauma, Publish ahead of print, January 21, 2016.